Right from about 1880 to his demise in 1904, Jamsetji was consumed by three great dreams for India: an iron and steel company, generating hydroelectric power, and a world-class educational institution that would tutor Indians in the sciences. None of these could materialize while Jamsetji lived, but the seeds he sowed, the toil he did, and the sheer force of will he demonstrated in fulfilling this triumvirate of his dreams, ensured they would soar high with an enigma to find expression.

Jamsetji was inspired to set up an iron and steel company, on his trip to Manchester, while attending a lecture by Thomas Carlyle. Come the 1880s, he had glued his heart on building a steel plant that would compare with the best of its kind in the world. Yes, the WORLD!

At the Tata Steel Archives in Jamshedpur, one can see the plans Jamsetji had created for the steel company he had dreamt of and relentlessly pursued for years. The plans include minute details of a bigger dream. The steel venture had become an important piece of his vision of an industrialized, independent India.

Of course, a dream this ambitious would not be without its challenges. The industrial revolution that had transformed Britain and other countries had, by and large, bypassed India. Officious government policies, the hostile investment environment of colonized India, the complexities of prospecting for steel in barely accessible areas and his own failing health— Jamsetji found his path blocked at every other turn by what his biographer, Frank Harris, called "those curious impediments which dog the steps of pioneers who attempt to modernize the East".

The Visitor

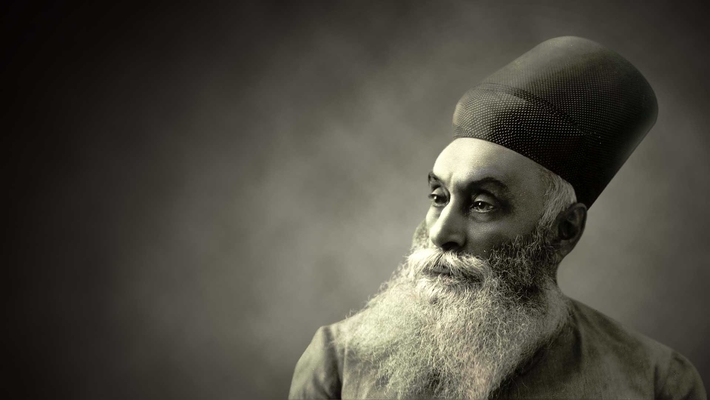

The door of a crowded office in New York opened wide. At the table surrounded by books, sat Charles Page Perin, a geologist and metallurgist, with wisdom of iron and steel that made him the most sought-after mogul. Sitting there poring over account books, there he was; there was nothing he liked less.

A voice said, “At last, I have found the man I’ve been looking for.” Perin listed his gaze off the books, pleasantly glad at the interruption, a little startled by the apparition standing tall before him. Here was a stranger in an even stranger attire— a man in a simple white coat wearing a rather peculiar headgear. He would later be able to identify the outfit as the Parsi dugli and pagdi. Who was he?

Even as he wondered, somewhere at the back of his mind, Charles Perin knew the answer. This man right there was the Parsi gentleman from India whose dream was to build a steel plant for his country; Julian Kennedy had written to him about him. For a long moment, the two men gazed at each other in silence, two men from different continents, poles apart in every way.

Charles' visitor said in a deep voice, “Are you Charles Perin?” The metallurgist nodded. And Jamsetji Tata said, “At last, I have found the man I’ve been looking for.” His communication was precise and pithy. “I have spoken to Mr Kennedy. He will build the steel plant — wherever you advise. And I will foot the bill. Will you come to India with me?” As Perin was to recall years later, he was dumbfounded, struck by the character, the force, and the kindliness that radiated from Jamsetji Tata’s face. Perin’s answer was short, “Yes,” he said, “yes, I will go with you.”

Finding Sakchi

Perin embarked on one of the most unusual adventures in his life. On his way, at Aden, he received a telegram asking him whether he could ride a bicycle. A bicycle? Mystified, he replied in the affirmative. He reached the village of Sakchi and discovered the reason for this strange question. Miles of rutted road stretched out before him, defying any conventional mode of transport. Several strenuous hours later, he found himself in the middle of the jungle, propping his bicycle with one hand and holding the twisted handlebar aloft with the other. Fortunately, a passing bullock cart came to his rescue.

There would be many more hurdles ahead. This was a harsh, demanding land, where the temperature could climb to 125º (F) in the shade. Heat waves made the land quiver as if with ague. Man-eating tigers and road elephants were treacherous adversaries, though on occasion a friendly bear would cub under a table. Cholera and malaria would sweep the hillside, causing workers to flee overnight in panic. It was tough going, but Perin and his team finally found more than they even dared to hope for — perhaps 3 billion tons of ore, located just 45 miles away from the railway station.

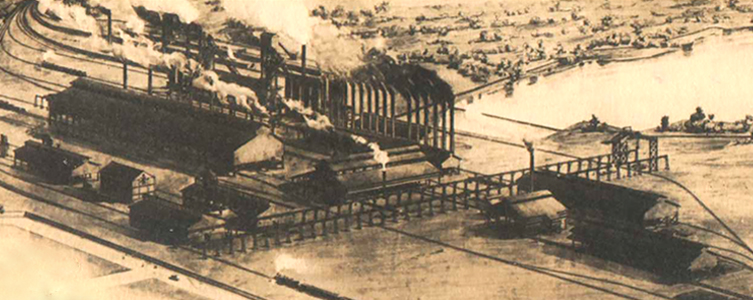

Unfortunately, Jamsetji would not see his dream—the one he had nurtured for 30 years—come to fruition. As a triumphant Perin was getting his report together, the sad news reached him. Jamsetji Tata had passed away in Germany. It fell on Jamsetji’s son, Sir Dorabji Tata, and his cousin RD Tata, to see his dream to completion. Tata Steel came into being in 1907 and held the distinction of being Asia’s first integrated steel company.

The torturous twists and turns the steel project took would have defeated lesser men, but Dorabji and RD Tata were steadfast in their determination to see Jamsetji’s dream come to fruition. Along the way, they had to suffer the scorn of people such as Sir Frederick Upcott, the chief commissioner of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway, who promised to "eat every pound of steel rail [the Tatas] succeed in making". There is no record of where Sir Frederick was when the first ingot of steel rolled out of the plant's production line in 1912. Jamsetji had been dead eight years by then, but his spirit it was, as much as the efforts of his son Dorab and cousin RD Tata, that made real the seemingly impossible.

Welfare at its Heart

Every generation of Tata Steel management and employees continues to live Jamsetji’s dream each day, translating his ideals into reality in everything they do. Nowhere is this more apparent than in their commitment to the welfare of employees, the community and the nation.

In fact, the brick-and-mortar endeavours that Jamsetji planned and executed were but one part of a grander idea. How much of a man of the future he was can be gauged from his views about his workers and their welfare. He spelt out his concept of a township for the workers at the steel plant in a letter he wrote to Dorab Tata in 1902, five years before even a site for the enterprise had been decided. "Be sure to lay wide streets planted with shady trees, every other of a quick-growing variety," the letter stated. "Be sure that there is plenty of space for lawns and gardens. Reserve large areas for football, hockey and parks. Earmark areas for Hindu temples, Mohammedan mosques and Christian churches." It was only fair that the city born of this sterling vision came to be called Jamshedpur.

In 1907, a hospital was built in Sakchi to bring much-needed medical care to the village, before the plant even started production

No surprise then, that even before the steel plant was set up in the remote little village of Sakchi, the company set up a hospital to bring much-needed medical care to the region. That was in 1908; the first ingot of steel rolled out of the Sakchi plant four years later, in 1912.

There were also several industry firsts in those early years: an eight-hour working day for labourers was introduced long before it became the norm around the world; free medical aid was introduced in 1915; the maternity benefit scheme was launched in 1928; the retirement gratuity scheme was introduced in 1937. It was even decided a few years later, that the families of contract workers suffering accidents at Tata Steel premises would be provided cover and benefits through a scheme called ‘suraksha’. All these welfare measures were well ahead of their times and implemented in the true spirit of empowering employees, so it is hardly surprising that the last workers’ strike settled in the company was as far back as 1929.

The War Years

The crushing urgency of World War I and the shortage of materials in Europe, thrust India into the forefront. Steel in large quantities was needed to construct railways to transport troops and supplies. Tata Steel stepped up. Its contributions were so significant that the then Viceroy of India, Lord Chelmsford, on his visit to the plant in 1919, “I can hardly imagine what we would have done if the Tata Company had not given us steel for Mesopotamia, Egypt, Palestine, and East Africa.” Sakchi was rechristened Jamshedpur, to honour founder Jamsetji Tata, and the steel city’s railway station, Kalimati, was renamed Tatanagar.

Tatanagars, used in desert warfare in North Africa, was built with armour hulls made by Tata Steel

When the next world war began, just two decades after WWI ended, Tata Steel pledged its entire output to the allied war effort.

Displaying exemplary ingenuity Tata Steel’s scientists produced 110 varieties of steel in only five years despite the hardships and shortages of war. Its other major achievements included the manufacture of 1,000 tonnes of armour plate per month from a mill setup in 1942 and the building of a benzol recovery plant in 1943 for producing toluene, which was used in producing explosives.

WWII also marked the start of the Tata group’s legacy of strategic partnerships with the Indian armed forces. A special plant of the Tata Engineering & Locomotive Company (TELCO) in Jamshedpur built an astounding 4,655 units of the Wheeled Armoured Carrier Indian Pattern or ACV-IP — popularly known as the Tatanagar — between 1940 and 1944. It played a prominent role as a forward observation and reconnaissance vehicle in the desert warfare in North Africa during WWII. It also saw action in the 1950 Korean war.

Steeled for the Future

From being a harbinger and, later, a symbol of Indian industrialisation and national pride, Tata Steel has evolved into an enterprise that has claimed its place in the global business space. The journey wasn’t easy, but the company stayed the course.

The turning point, clearly, came in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, when India’s economic liberalisation forced the company to revisit its business processes, including its approach to quality and customers. Tata Steel took the challenge head on, emerging a smarter, wiser and more agile entity.

Over the last decade, the company has taken to the global stage with the same zeal that once made it a national entity. A string of acquisitions, starting with NatSteel in 2004 and leading up to Corus in 2008, have seen Tata Steel take not only itself but the larger Tata brand to the fore in international business circles. 2018’s joint venture with Thyssenkrupp promises to transform the company into a leading pan European high quality flat steel producer with a strong focus on performance, quality and technology leadership.

Through it all, the company continues to be driven by Jamsetji’s vision. From nation-building, it has grown into an enterprise that is committed to building every nation and community in which it operates, pursuing this goal with the same steely determination that drove Jamsetji to achieve the impossible.